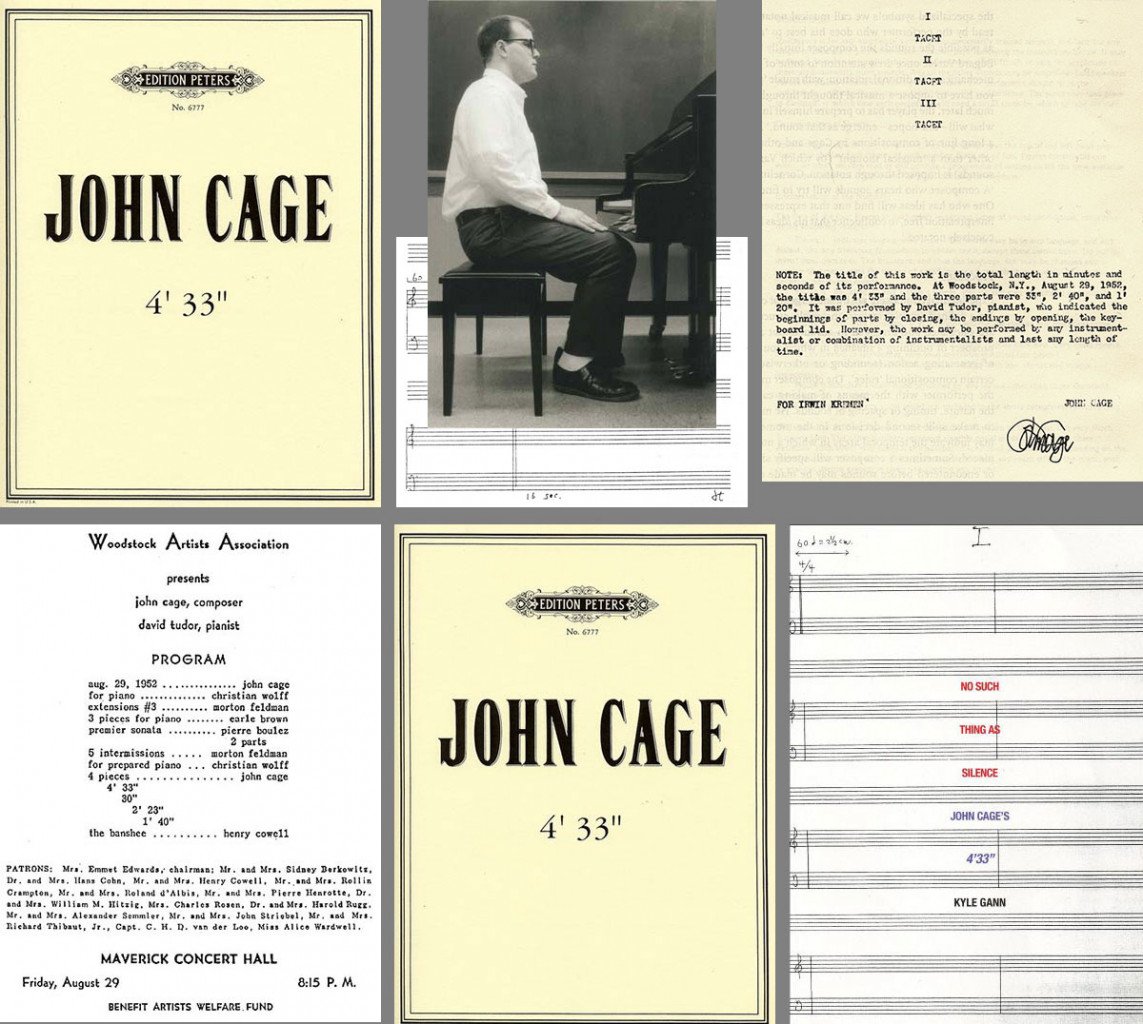

"'Εχασαν το νόημα. Η σιωπή είναι κάτι που δεν υπάρχει. Το πρώτο που σκέφτηκαν ήταν η σιωπή επειδή δεν ήξεραν πως να ακούσουν, πως να συλλάβουν όλους αυτούς τους τυχαίους ήχους που πλημμύριζαν το χώρο. Θα μπορούσες στο πρώτο μέρος να ακούσεις τον αέρα. Στο δεύτερο, οι σταγόνες της βροχής άρχισαν να χτυπούν την οροφή, και στο τρίτο οι ίδιοι οι άνθρωποι δημιούργησαν πολλούς ενδιαφέροντες ήχους καθώς μιλούσαν ή έβγαιναν από την αίθουσα."

(Ο John Cage για την πρεμιέρα του 4′33″).

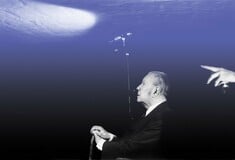

Η ανάμνηση του έργου 4'33" από τον πιανίστα -και συνθέτη πειραματικής μουσικής- David Tudor. "[…] Ο κόσμος άρχισε να ψιθυρίζει, μερικοί βγήκαν από την αίθουσα. Κανείς δεν γέλασε, οι θεατές εκνευρίστηκαν όταν κατάλαβαν ότι δεν επρόκειτο να συμβεί τίποτα και δεν το ξέχασαν τριάντα χρόνια μετά : παραμένουν ακόμη θυμωμένοι."

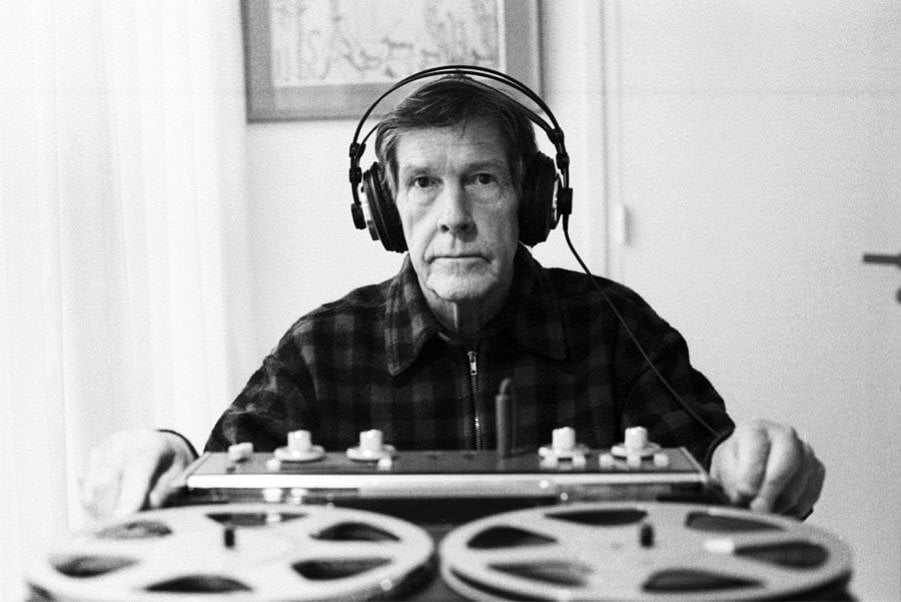

Φωτ. Paul Kilbey.

Το 2010, μία ομάδα στο Facebook ζήτησε να αγοραστεί μαζικά το 4'33" για να εμποδίσει το σάουντρακ της σειράς The X Factor να έρθει πρώτο στα UK Singles Chart και να ξημερώσει έτσι μία σιωπηλή 25 Δεκεμβρίου. Μία παρόμοια ενέργεια είχε εξασφαλίσει την προηγούμενη χρονιά τον θρίαμβο του συγκροτήματος Rage Against the Machine. Η ομάδα "Cage Against the Machine" έφτασε να έχει πάνω από 85.000 μέλη.

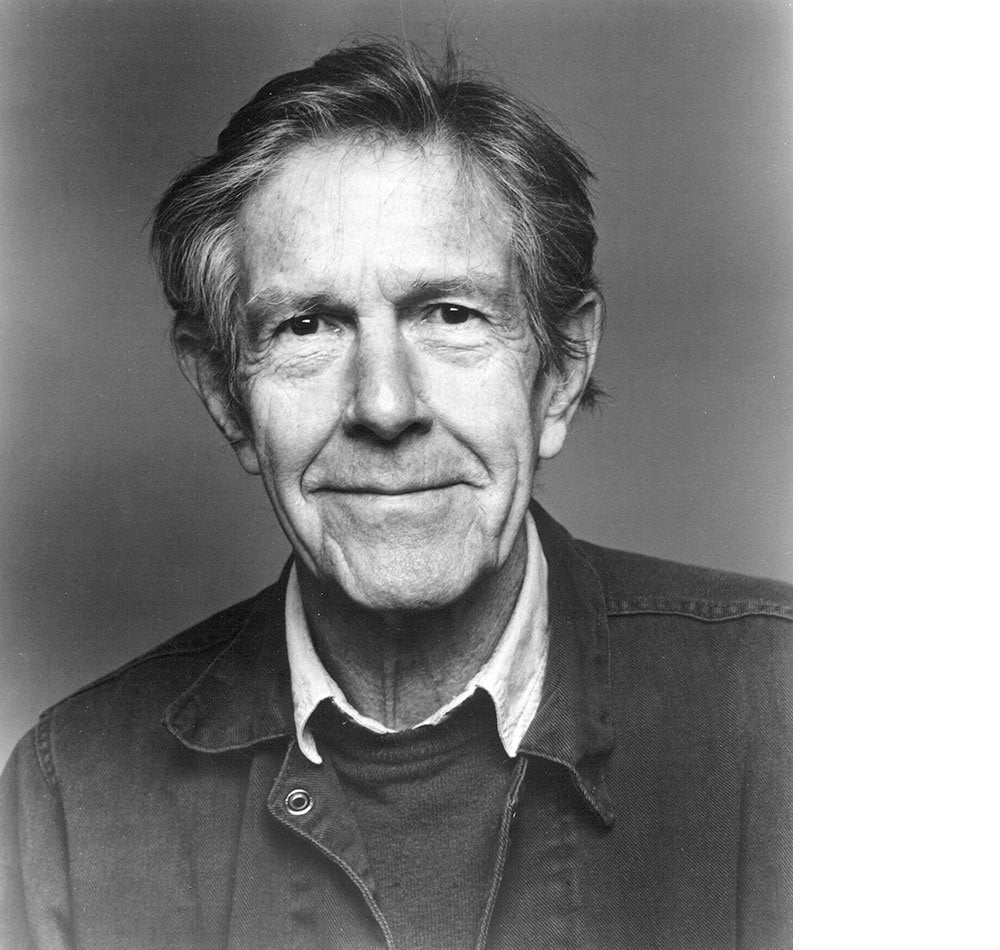

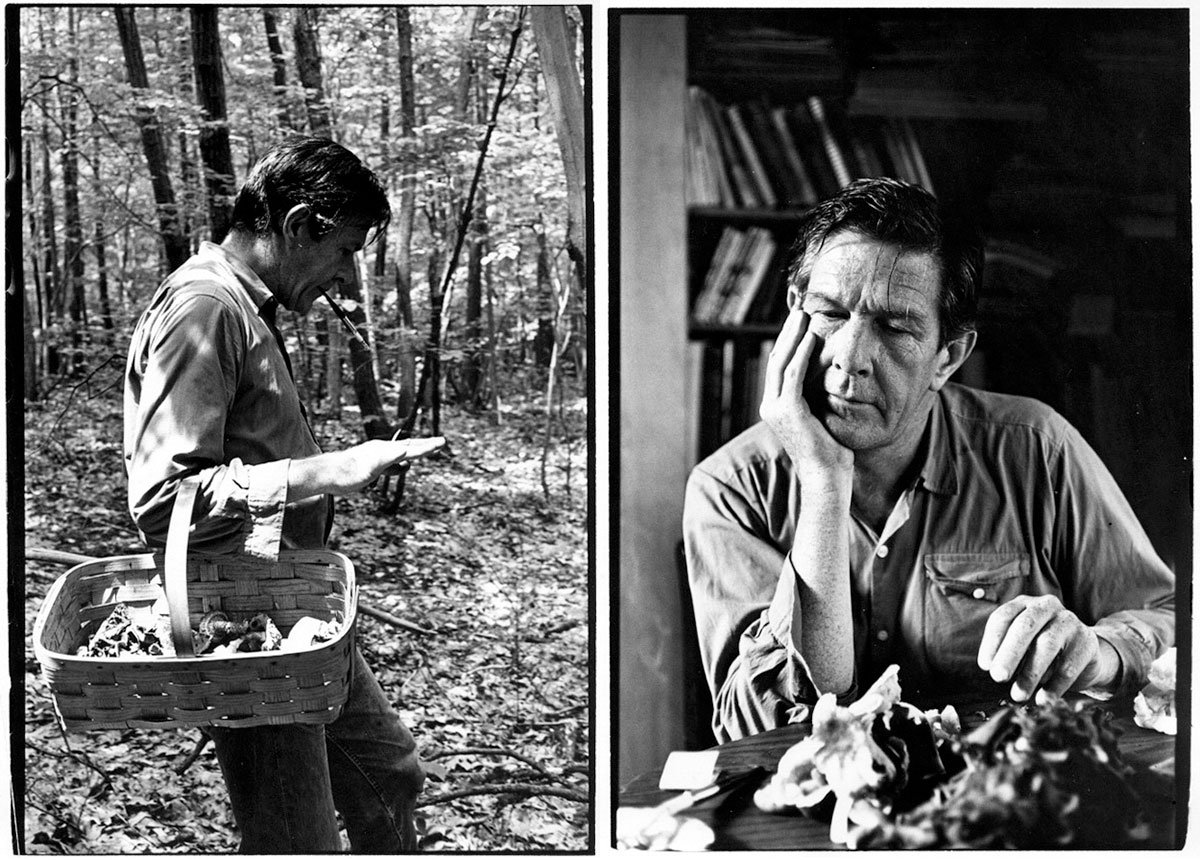

Φωτ. William Gedney, Duke University Libraries.

"Sound" (1966-67), σε σκηνοθεσία Dick Fontaine . Ο John Cage θέτει ερωτήματα γύρω από τους ήχους και τη μουσική. Μαζί του στην ταινία οι Rahsaan Roland Kirk και David Tudor.

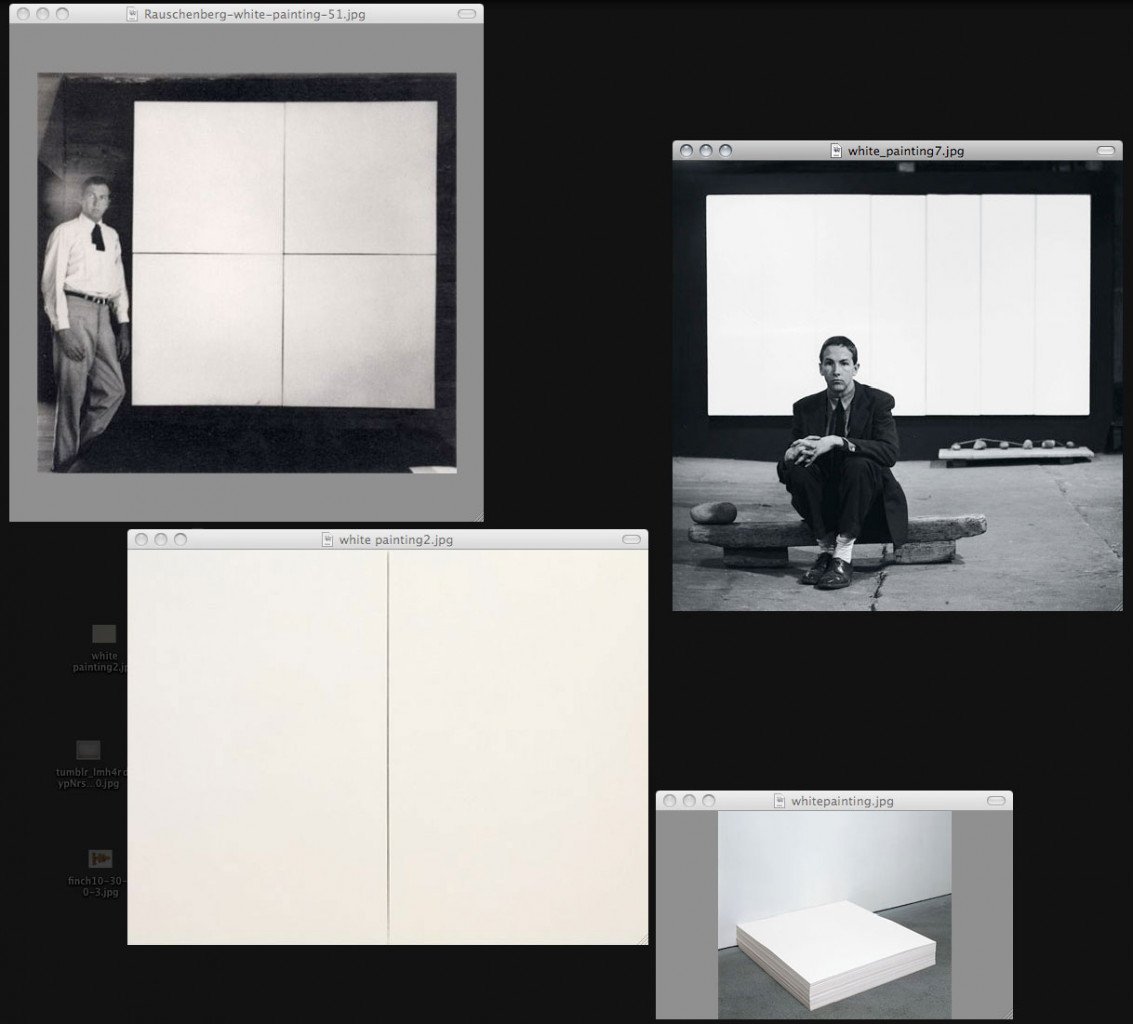

Εκτός από την εμπειρία που είχε το 1948 μπαίνοντας σε έναν ανηχοικό χώρο του Πανεπιστημίου του Harvard, μεγάλη οπτική επίδραση άσκησε πάνω στον John Cage για τη δημιουργία του έργου του 4'33" μια σειρά από λευκούς πίνακες του φίλου του ζωγράφου Robert Rauschenberg (White Paintings). Αυτή την ιδέα του κενού που "γεμίζει" ανάλογα με την ώρα, την εποχή η τις σκιές των ανθρώπων θέλησε να μεταφέρει ο Cage και στη μουσική.

Φωτ. William Gedney, Duke University Libraries.

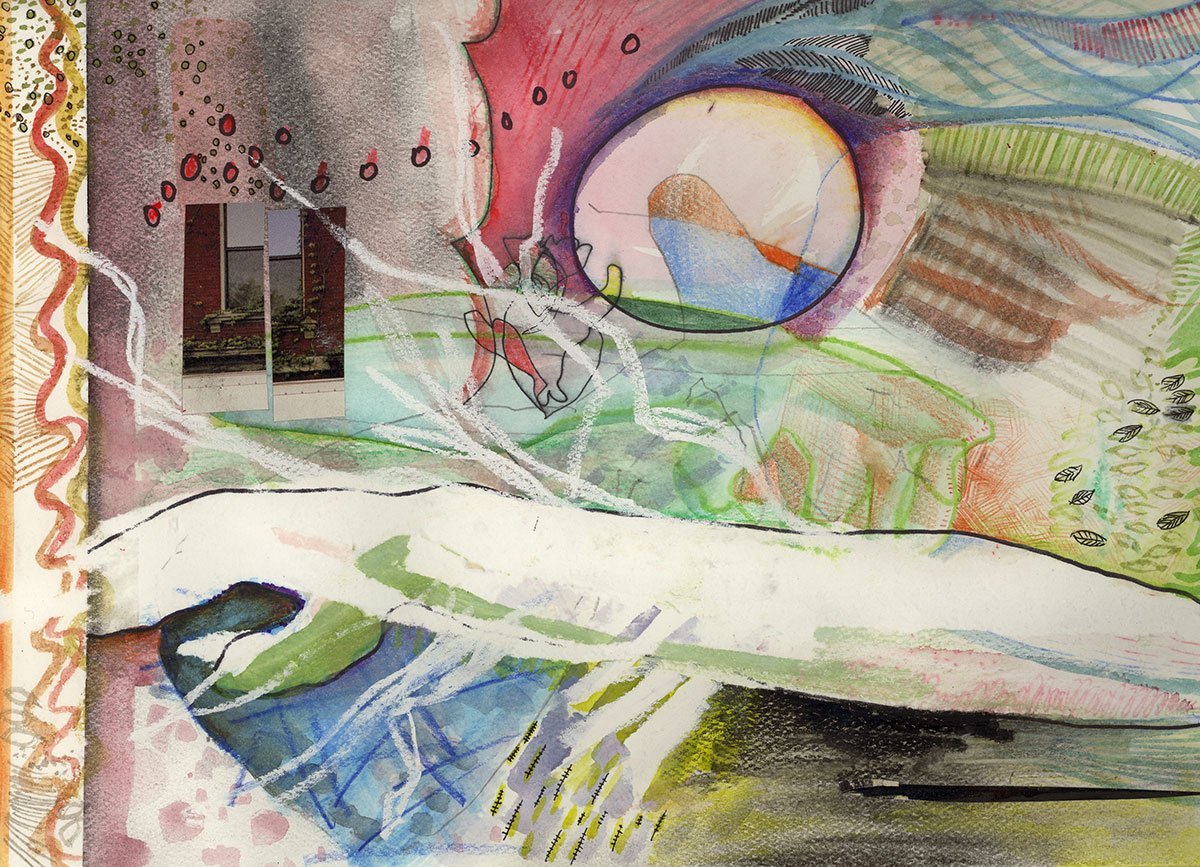

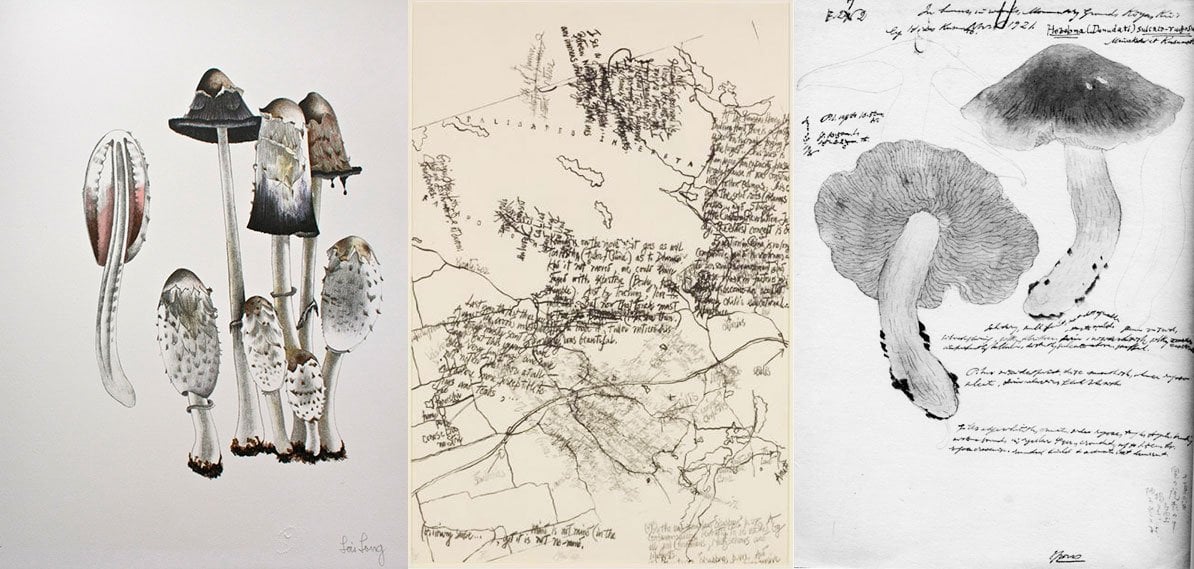

'Εργα ζωγραφικής του John Cage. Ξανάρχισε να ζωγραφίζει από το 1969.

John Cage at The Barbican. Η Συμφωνική Ορχήστρα του BBC με μαέστρο τον Laurence Foster ερμηνεύει σε πλήρη διάταξη το έργο 4'33".

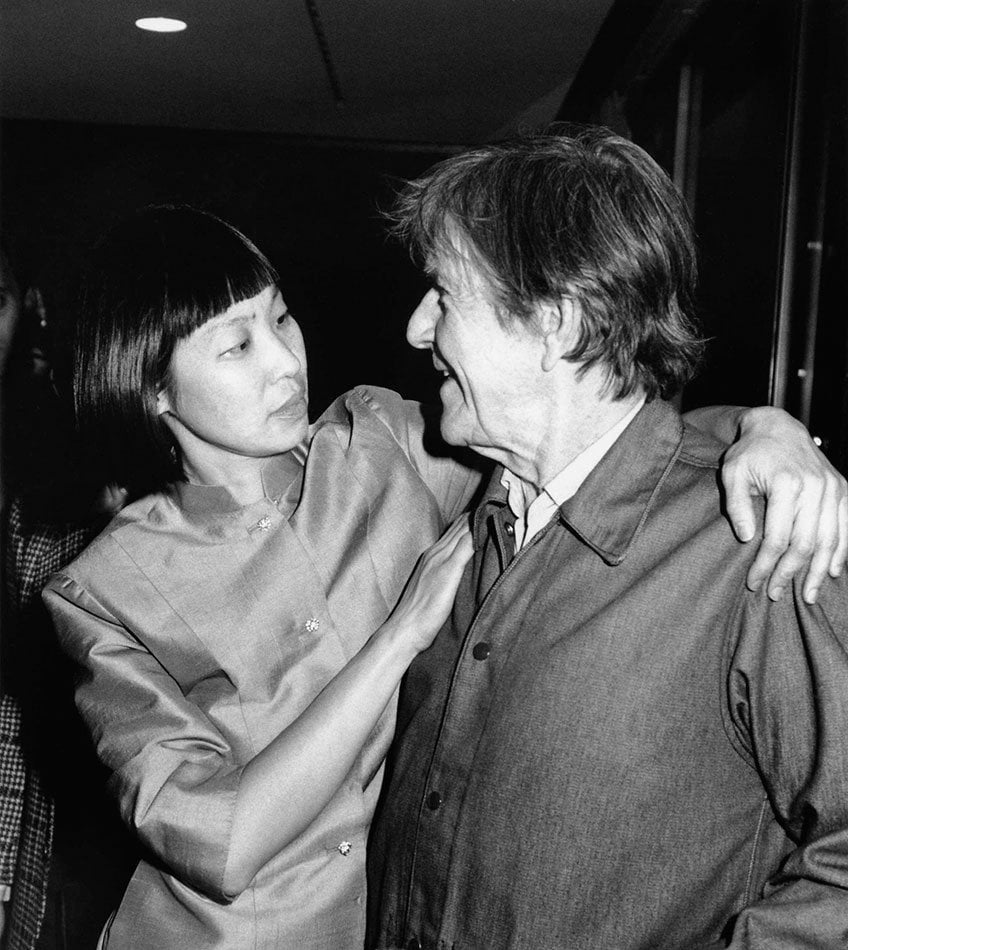

Θερμή υποδοχή από την πιανίστρια Margaret Leng Tan, την αποκαλούμενη από το περιοδικό The New Yorker "diva of avant-garde pianism". Φωτ. George Hirose.

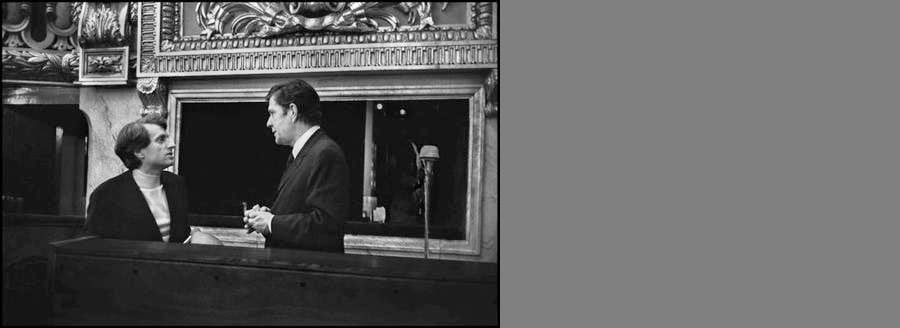

Με τον Γιάννη Ξενάκη. "Αναρωτιέμαι αν ο Ξενάκης είναι πολύ μακριά από αυτό που προσπαθώ να κάνω - όχι βέβαια σε ό, τι λέει, αλλά σε αυτό που επιτυγχάνει." - John Cage (συνέντευξη στον Daniel Charles).

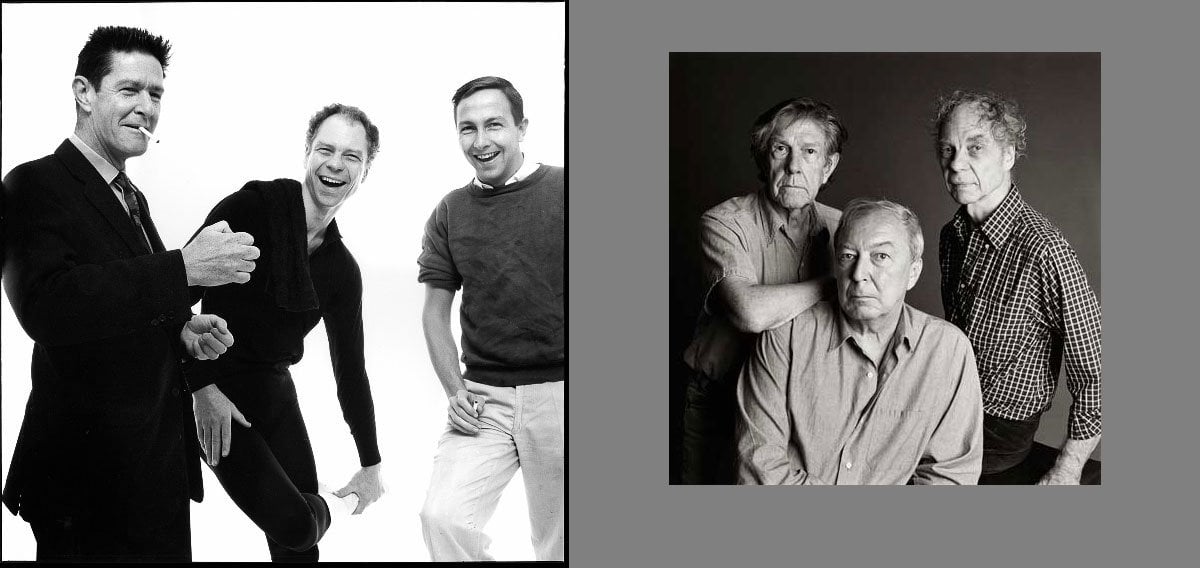

Αριστερά, στη φωτογραφία του Richard Avedon, ο John Cage με τους Merce Cunningham και Robert Rauschenberg (Μάης του1960, Νέα Υόρκη). Δεξιά, στη φωτογραφία του Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, είναι μαζί με τους Jasper Johns και Merce Cunningham (Ιούλιος του 1989).

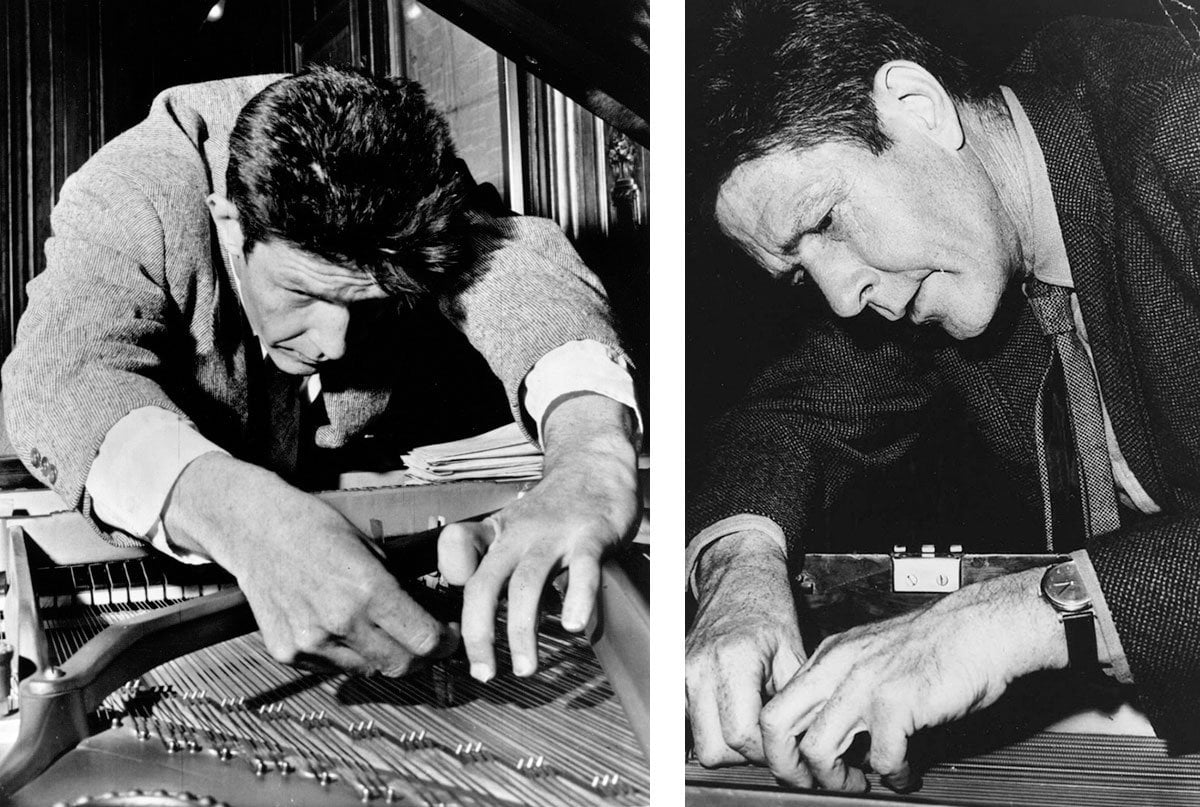

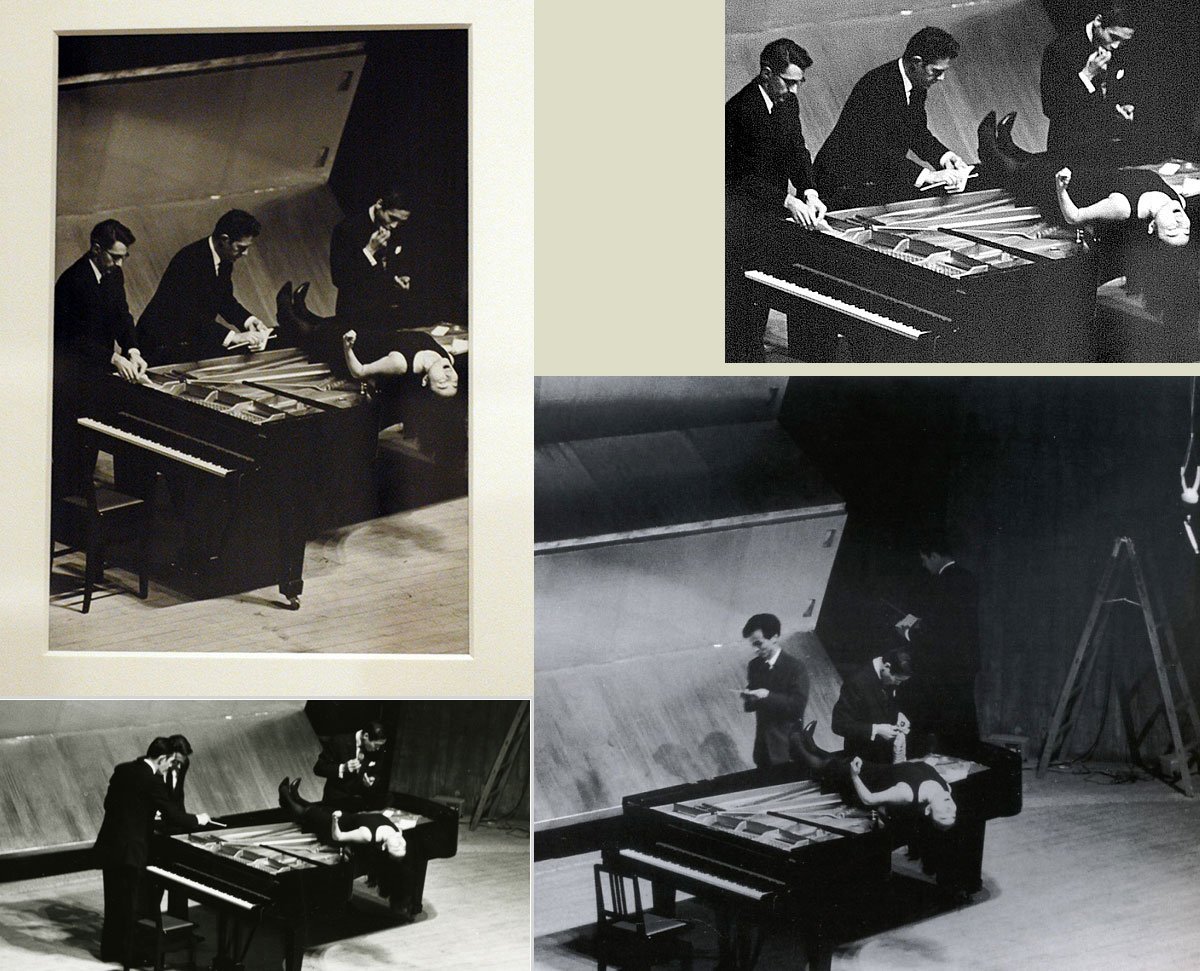

"Ετοιμάζοντας" το πιάνο.

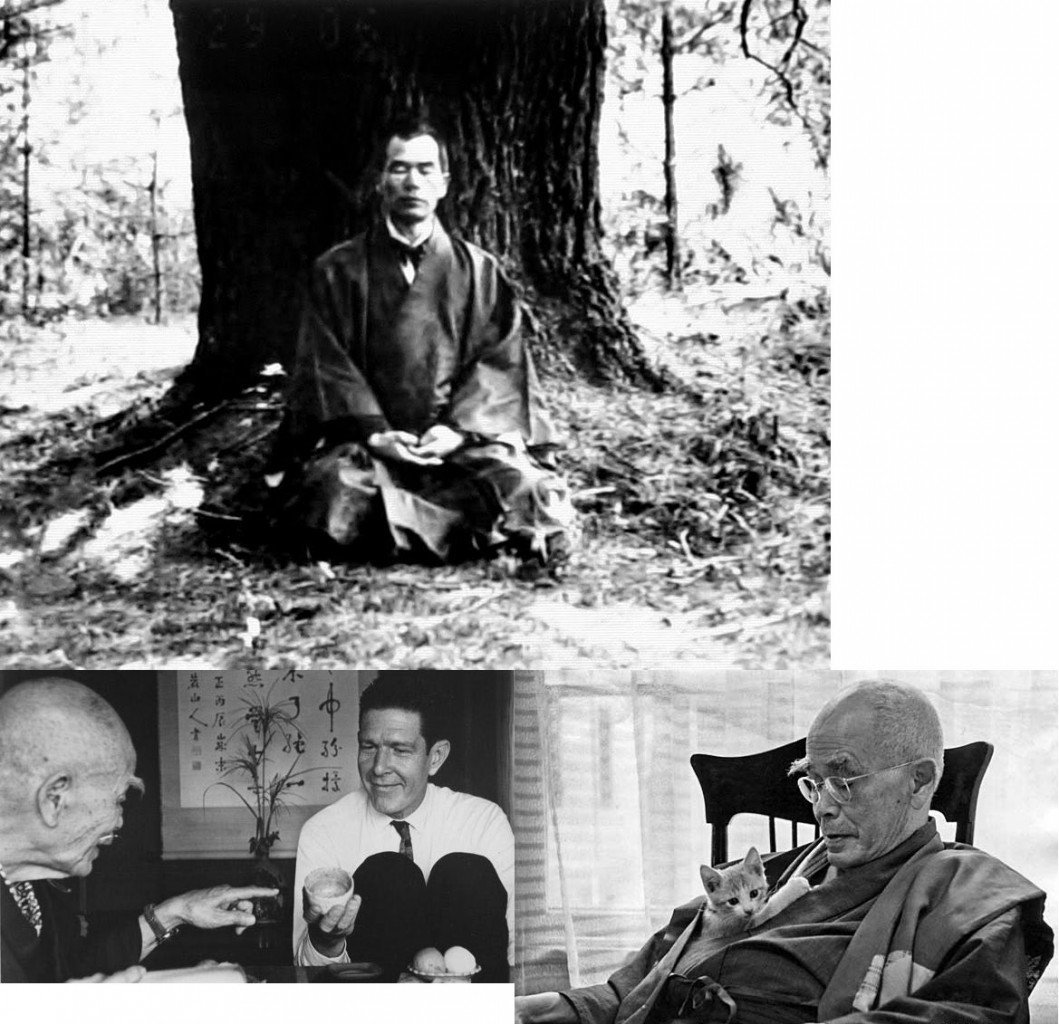

A Zen Life - D.T. Suzuki, ντοκιμαντέρ που ανήκει στη σειρά του NBC "Conversations with Elder Wise Men" (1957-1965).

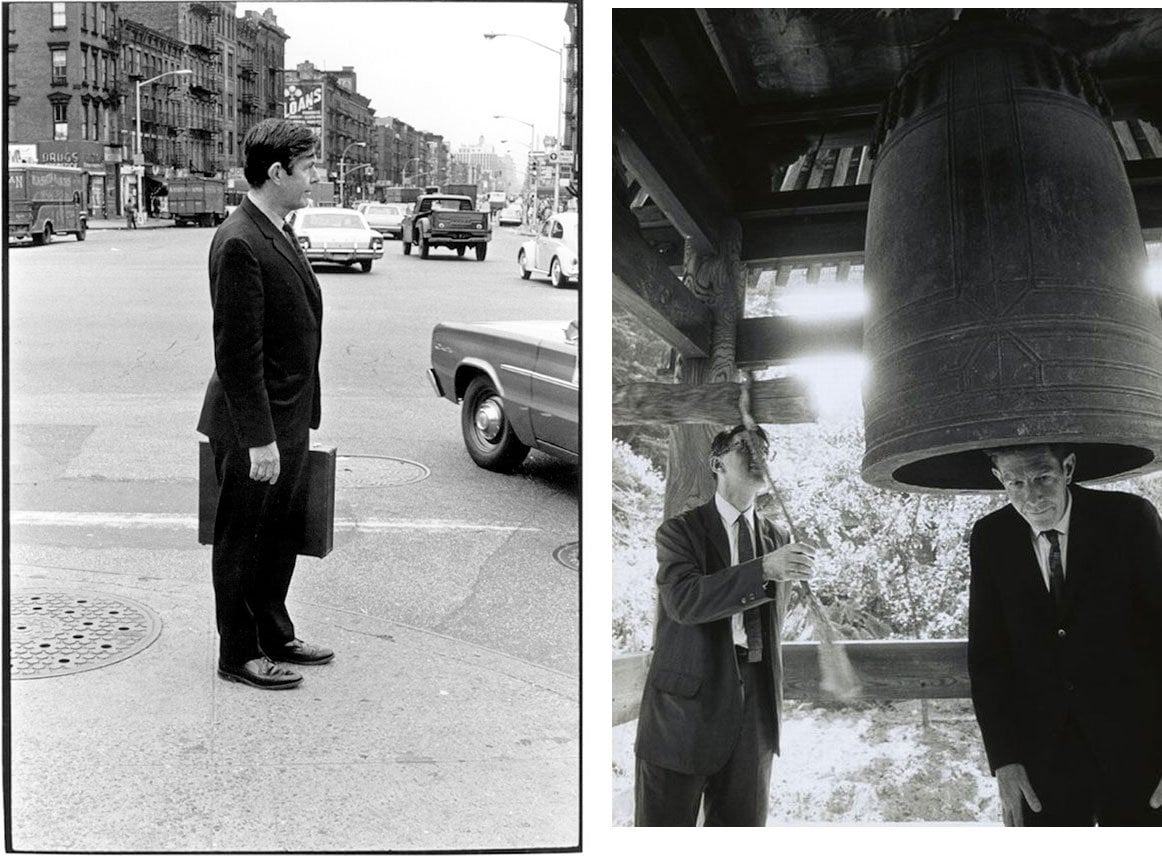

Ο John Cage με τον καθηγητή D.T. Suzuki που είσήγαγε στη Δύση μία μοντερνιστική θεώρηση της ζεν βουδιστικής πρακτικής και φιλοσοφίας. Ο Cage ήταν ένθερμος αποδέκτης αυτής της φιλοσοφίας ζωής.

Zen Ox-Herding Pictures, Set One, Number 3 και 9 (1988), υδατογραφίες του John Cage επιρρεασμένες από την παράδοση του Ζεν. 1988. Ιδιωτική συλλογή.

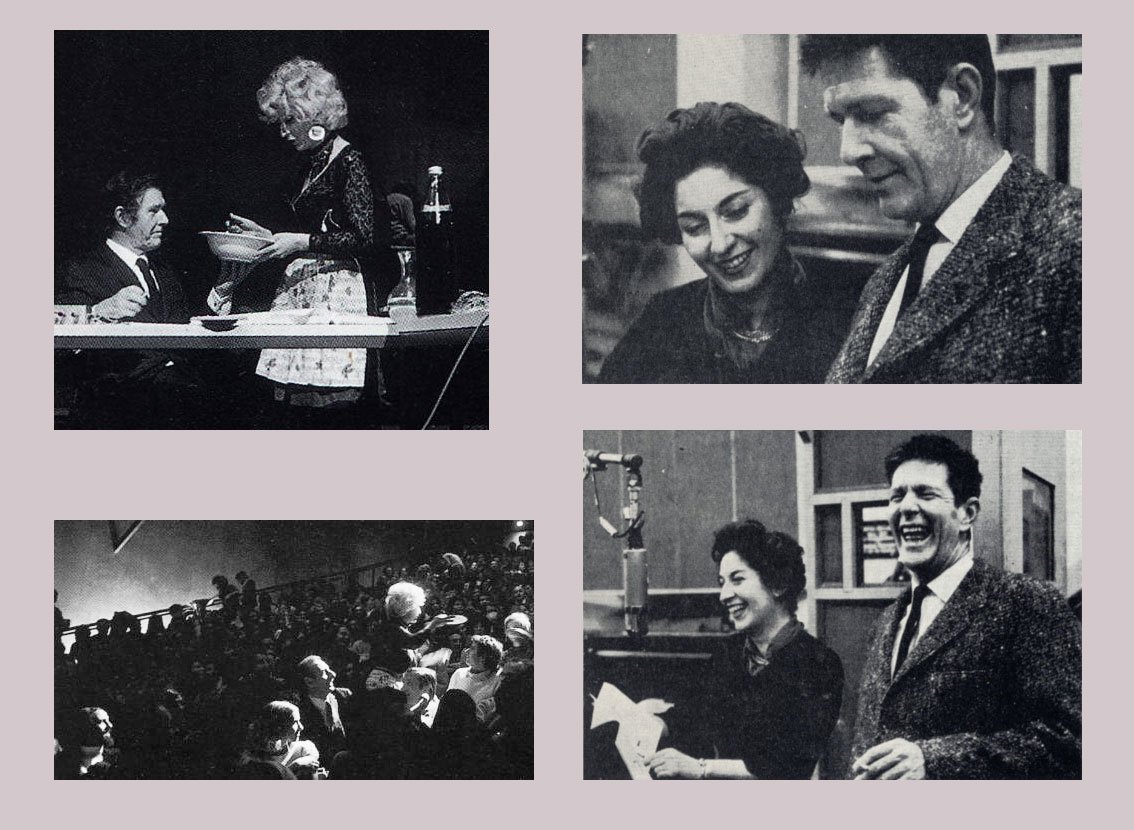

Water Walk, μία περφόρμανς του John Cage το Γενάρη του 1960 μπροστά στο τηλεοπτικό κοινό της πετυχημένης εκπομπής I've Got A Secret. Το κοινό ξεκαρδίστηκε και χειροκρότησε.

A Flower, έργο του John Cage, για φωνή και κλειστό πιάνο (1950). Τραγουδάει η Cathy Berberian, αντικονφορμιστική λυρική τραγουδίστρια αρμενικής καταγωγής. Ζωντανή ηχογράφηση στη Βενετία το 1967.

Με την Cathy Berberian στην πρώτη τους περφόρμανς (1970), μέρος των "Song Books" (Ninety Solos for Voice). Η Cathy Berberian ζητάει από τον Cage που κάθεται στην σκηνή να δοκιμάσει τα μακαρόνια που έχει φτιάξει προτού τα μοιράσει στο κοινό. Φωτ. Philippe Gras/Cristina Berio.

Μία περφόρμανς το 1968 από τους David Tudor, John Cage, Yoko Ono και Mayuzumi Toshiro.

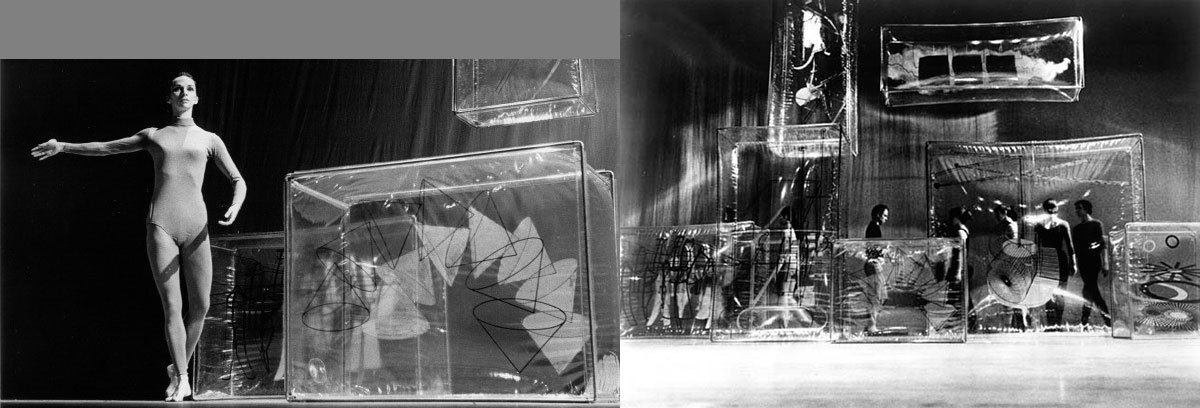

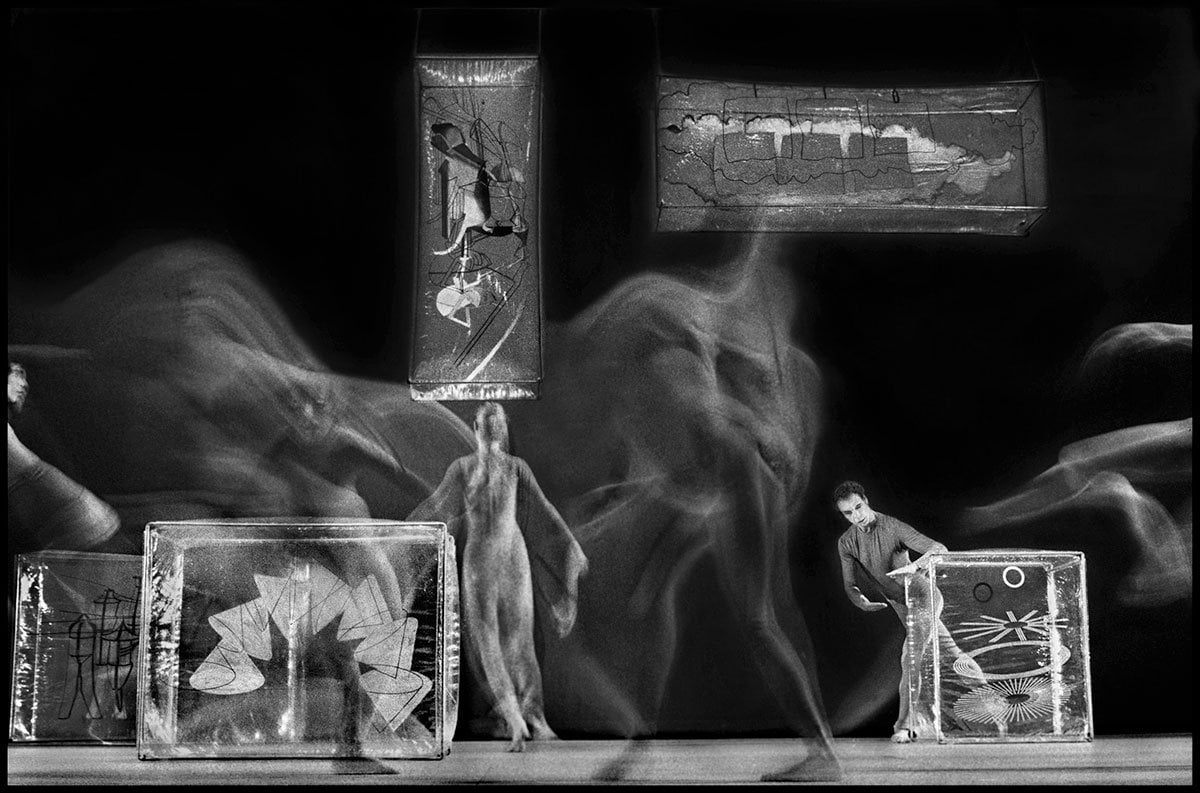

Variations V, μουσική John Cage, χορογραφία Merce Cunningham. Ο Merce Cunningham συνεργάστηκε ανελλειπώς με τον John Cage, ο οποίος ήταν και ο συντροφός του στη ζωή, από την ίδρυση της Merce Cunningham Dance Company μέχρι το θάνατο του Cage to 1992.

Walkaround Time, χορευτικό έργο που δημιούργησαν από κοινού ο John Cage με τον Merce Cunningham το 1968.

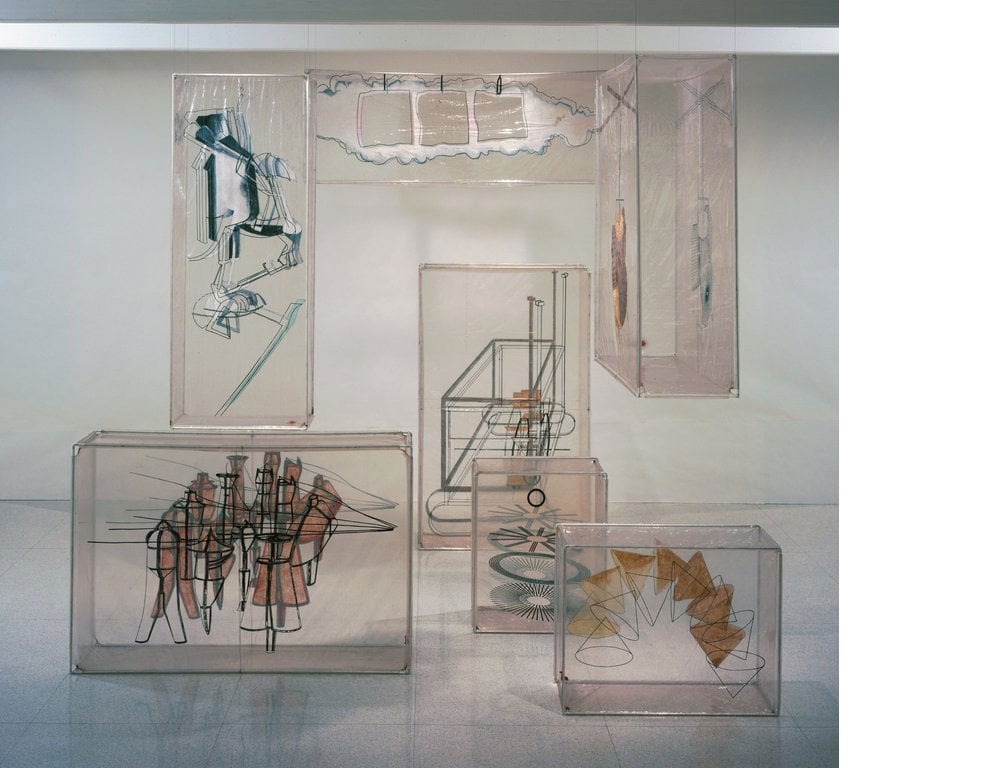

Walkaround Time, σκηνικά του Jasper Johns : επτά φουσκωτά πλαστικά μαξιλάρια ζωγραφισμένα με είκονες παρμένες από το έργο του Duchamp "The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even" (The Large Glass).

Walkaround Time, φωτογραφία από την παράσταση στο Παρίσι το 1970.

Dreams That Money Can Buy (1947), ταινία-ορόσημο του κινηματογραφικού υπερρεαλισμού που οφείλεται στη συνεργασία του Hans Richter με τους Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Jean Cocteau, Paul Bowles, Fernand Leger, Alexander Calder. Η μουσική που συνοδεύει την "παρέμβαση" του Marcel Duchamp είναι του John Cage.

Στις 5 Μαρτίου του 1968, ο John Cage και ο Marcel Duchamp πραγματοποίησαν μία σκακιστική περφόρμανς στο Ryerson Theatre του Toronto που την ονόμασαν "Reunion". Ο Duchamp κέρδισε σχεδόν αμέσως την πρώτη παρτίδα, αλλά η δεύτερη με αντιπάλους τον John Cage και την Teeny, τη γυναίκα του Duchamp, κράτησε πάνω από 4 ώρες. Φωτ. Musicworks Magazine (via Fluxlist).

Rotoreliefs, έργα του Marcel Duchamp. Σχέδια ζωγραφισμένα πάνω σε στρογγυλά χαρτόνια που δίνουν μία τρισδιάστατη αίσθηση όταν περιστρέφονται σαν δίσκοι 33 στροφών πάνω σε ένα γραμμόφωνο.

Rotoreliefs, έργα του Marcel Duchamp. Σχέδια ζωγραφισμένα πάνω σε στρογγυλά χαρτόνια που δίνουν μία τρισδιάστατη αίσθηση όταν περιστρέφονται σαν δίσκοι 33 στροφών πάνω σε ένα γραμμόφωνο.

Φωτ. William Gedney, Duke University Libraries.

Mushroom Book, 1972, λεύκωμα τυπωμένο στο χέρι με λιθογραφίες των John Cage και Lois Long και κείμενο του Alexander H. Smith. Εκδόσεις Hollander Workshop, Inc., Νέα Υόρκη.

One11 with 103 (1991-1992), η μοναδική ταινία που γύρισε ο John Cage λίγο πριν πεθάνει, χωρίς θέμα, πρόσωπα η ιδέες. Μόνο ασπρόμαυρο φως.

Συνέντευξη του John Cage στη Laurie Anderson (από το βιβλίο του Robert Coe: The Emergence of the American Avant-garde. εκδ. W.W. Norton).

Laurie Anderson : You seem like such a hopeful person, do you think human beings are getting better?

Cage: What can we say but yes. There's no other answer.

A: To go on? To be able to go on?

C: Not to be able to go on, but to go on. As D.T. Suzuki said once, "There seems to be a tendency toward the good." Isn't that beautiful? There seems to be a tendency toward the good. He never explained what he meant. And we never asked him.

A: What led you to study with him?

C: I was very fortunate. I had readThe Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna.I became interested, in other words, in Oriental thought. And I read also a short book by Aldous Huxley, calledThe Perennial Philosophy,and from that I got the idea that all the various religions were saying the same thing but had different flavors. For instance, Ramakrishna spoke of God as a lake of people coming to the shores because they were thirsty. So I browsed, as it were, and found a flavor I liked and it was that of Zen Buddhism. It was then that Suzuki came to New York, and I was able to go to Columbia once a week for two years to attend his classes, which were, if I remember correctly, at 4:30 in the afternoon.

A: Pleasant time of day.

C: Suzuki was not very talkative. He would frequently say nothing that you could put your finger on. Now and then he would. When I say now and then I mean one Friday or another, but on any given day, nothing that you could remember would remain.

A: Did you ask questions?

C: I don't remember doing that. C: Once in Hawaii, at a meeting of philosophers sitting around a table discussing reality, several days passed and Suzuki said nothing. And finally the chairman said, "You've been silent all this time. Would you say something about reality." And Suzuki didn't say anything. I think he may have looked up. Finally the man said, "Well, is this table real?" And Suzuki said "Yes." And then the man said, "In what sense is it real?" And Suzuki said, "In every sense."

A: When the Dalai Lama was at Madison Square Garden [for the Kalachakra initiation in October, 1991] a lot of people asked him questions but they were not questions. They were really things to show him what they knew. So you'd listen to these questions and the people asking them didn't want to know anything. Then came the last question. The Dalai Lama was on a big stage with all the lamas and there was a big golden pagoda on the stage, closed. All these people were asking questions, very esoteric questions about Buddhism, and he was being very generous about answering them. But the best question was, "What's in the yellow pagoda?" It was such an obvious question. This big thing was sitting there and no one would ask what was inside of it. He just described what the sand painting was like that they were working on inside. And it changed everything. It was the only honest question at the Kalachakra....The teachings were tricky. They would almost trick people into taking vows. I took one. I promised to be kind for the rest of my life. I walked out the door and said what does this mean? Then a friend got a hold of a monk, and she said, "Did I promise too much, too little?" He told her, "You know, the mind is a wild white horse, and when you build a corral for it, make sure it's not too small." He was so practical. The Dalai Lama was saying that he felt very fortunate to have earned so many merits in his past live, and that was the reason he was having such an enjoyable life....Do you feel that someone before you gathered merits so that you could have an enjoyable life or that you're gathering ones so that someone, your descendants, can have one too?

C: I don't have any knowledge of that.

A: So you're not curious?

C: I'm not curious.

A: In using chance operations, did you ever feel that something didn't work as well as you wanted?

C: No. In such circumstances I thought the thing that needs changing is me-you know-the thinking through. If it was something I didn't like, it was clearly a situation in which I could change toward the liking rather than getting rid of it.

A: Would you think of it as a kind of design whose rules you just couldn't understand?

C: I was already thinking of one rather than two, so that I wasn't involved in that relationship. And that what was actually annoying me was the cropping up of an old relationship, which seemed at first to be out of place. But then, once it was accepted, it was extraordinarily productive of space. A kind of emptiness that invites, not what you are doing, but all that you're not doing into your awareness and your enjoyment.

A: So you did, in fact, make a kind of judgment on yourself.

C: Yes, instead of wiping out what I didn't like, I tried to change myself so I could use it. C: The big difference between the city and the country is the sound of traffic and the sound of birds. Actually, I find the sound of traffic not as intruding, really, as the sound of birds. I was amazed when I moved to the country to discover how emphatic the birds were for the ears.

A: You mean they range in melody?

C: No. Because they were so loud. And they really compete with the sirens when they fly around and come close...C: I keep manuscripts that are clearly no good because they must have some reason for existing too.

A: In what sense do you mean no good?

C: Not interesting. Where the ideas aren't radical, where they don't have likeliness or-what Bob Rauschenberg says-"they don't change you." And I think that the idea of change, or the ego itself changing direction, is implicit in Suzuki's understanding of the effect of Buddhism on the structure of the mind. I use chance operations instead of operating according to my likes and dislikes. I use my work to change myself and I accept what the chance operations say. The I Chingsays that if you don't accept the chance operations you have no right to use them. Which is very clear, so that's what I do.

A: How has the response to your work changed over the years?

C: Well, I don't have to persuade people to be interested. So many people are interested now that it keeps me from continuing really. I asked a former assistant a few days ago how I should behave about my mail that is so extensive and takes so much time to answer? If I don't answer it honorably, I mean to say, paying attention to it, then I'm not being very Buddhist. It seems to me I have to give as much honor to one letter as to another. Or at least I should pay attention to all the things that happen.

A: What did you decide to do about it?

C: To consider that one function in life to answer the mail.

A: But it could take the whole day.

C: But you see, in the meanwhile, I've found a way of writing music which is very fast. So that if we take all things as though they were Buddha, they're not to be sneezed at but they're to be enjoyed and honored.

A: But this is a huge challenge.

C: It's a great challenge. The telephone, for instance, is not just a telephone. It's as if it were Creation calling or Buddha calling. You don't know who's on the other end of the line.

C: The question of social activism is a large question because it has so many different kind of actions. I prefer to do what I'm doing for itself rather than to do what I'm doing for another reason. If I want to help say, getting rid of AIDS, it would seem to me more effective to support the research than to change the music.

A: Yeah, although a lot of artists say the opposite. They say, "Well, I'm going to work on it in my own way in my work." How does that convince people or help them? I think giving money to research is so practical.

C: That's how I do it. Rather than complaining about the politics, I think that we should become actively disinterested in government. It seems to be the most active thing to do now.

A: It's been so confusing to me the last few months trying to get involved in politics and going "I don't know....really I'm not very good at is." And yet, I can't say I should just do it in my work.

C: No, I think you can. I think your work is very, very important and very much used by society. This is the marvelous thing. Because you can perform and be seen, you see. I mean, the flow is taking place and you can increase it.

A: For me, being in a political group, particularly a women's group, is sort of like answering mail. I feel that I should do this-I should be there.

C: It gives you a sense of responsibility.

A: Yeah.

C: But your real responsibility is the one that you discover. However you work. Your best work is what you yourself discover.

Σημειώνουμε, τέλος, και δύο εξαιρετικά άρθρα του 'Αλκη Γαλδαδά σχετικά με το θέμα που βρίσκει κανείς εύκολα στο διαδικτυακό αρχείο του Βήματος :

- Τα αρχαία θέατρα «κουρδίζονταν»!

Πώς τα αρχαιοελληνικά και ρωμαϊκά θέατρα άγγιζαν την ακουστική τελειότητα.

ΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ: 14/06/2011

-Ηigh-tech κάθοδος στον... Αδη.

Ενα θαύμα ακουστικής αποτελεί η αίθουσα του «Κάτω Κόσμου» στο Νεκρομαντείο του Αχέροντα δημιουργώντας την απαραίτητη απόκοσμη εντύπωση, μαζί και με άλλα τεχνολογικά τρικ των αρχαίων Ελλήνων που δεν υστερούν σε τίποτε από εκείνα του Κόπερφιλντ.

ΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ: 17/11/2008

σχόλια